Since this essay covers the earliest recorded instance of Kate Bush collaborating with other artists, now seems like a good time to thank the people who’ve helped me out on this blog. So infinite thanks to William Shaw, Michelle Coats, and the author of this great article for proofreading these essays, and also thanks to Tomer Feiner for straightening me out on the music theory for this one. Y’all are fantastic.

Need Your Loving (demo)

Passing Through Air

Having a professionally recorded song makes our job much easier. What nuances are lost in the lo-fi recordings of, say, “Queen Eddie” or “Sunsi” are picked up in the clean sound of “Passing Through Air.” This is largely due to Cathy recording with professional equipment for the first time. She didn’t need it to shine before, of course—she’s simply honing her best work to date for a really, really important moment.

Artists rarely get a big break. A 15-year-old artist’s home demos getting picked up for professional recording was pretty much unheard of in the pre-Soundcloud age. For a young artist to be discovered by a musician coming off the back of releasing one of the bestselling albums of all time seems colossally unlikely. Yet this is an exaggeration—plenty of people had heard Cathy’s demos by this point, and she wasn’t the only artist David Gilmour had taken under his wing at the time. Coming off The Dark Side of the Moon’s massive success, Gilmour was nurturing about eight protégés, the luckiest of whom would hit #1 on the UK singles charts five years later. He’d found Kate via her brother Jay’s friend Ricky Hopper, who played Gilmour some tapes which struck him. Maybe it was the undercurrent of ethereal strangeness in Kate’s songs or her musical aptitude which struck him. After he’d worked on “The Great Gig in the Sky,” no wonder he was into this sort of thing.

Another Gilmour ward was the band Unicorn, featuring the rhythm section of bassist Pat Martin and drummer Pete Perrier. The two musicians readily agreed to record the Bush sessions (they did so without immediate payment, although they’d receive royalties when the song was released seven years later.) They proceeded to play a number of songs (the exact song count is lost to history), including “Maybe” and “Passing Through Air.” The accompaniment of Gilmour, Martin, and Perrier, while not daring or spectacular by any means, lends some musical texture to “Passing Through Air.” To date, Cathy’s songs have sounded like they were recorded in a vacuum, not just because of their sound quality, but in how they’re completely isolated from any human contact. Gilmour’s home studio is a huge step up for her—being able to work with an 8-track recorder, a 16-channel mixing desk, an upright piano, and a Wurlitzer electric piano must have been thrilling for her. She immediately takes advantage of the equipment—she seems to record her vocal with automatic double-tracking (two tracks of audio will be recorded simultaneously, but one will have a slight delay, giving the recording a thick, rich sound. John Lennon used this technique often). Cathy steps into the world of professional recording with impressive ease, and so she makes our job a little easier as well. Not only do we know the exact circumstances under which “Passing Through Air” was recorded and have a high-quality recording of the song—there’s even sheet music for it.

The seminal book Kate Bush Complete helps us out enormously here. Published by EMI in 1987, the text eschews the erroneous notation which plagues most sheet music books in favor of transcribing the song as heard on record. A cursory scan of Complete’s entry for this song shows that “Passing Through Air” is a weird composition. The verse begins with a single bar in A before walking through the VI and i chords of A minor (F major and A), followed by the III chord (C), a slash chord (C/B), and resolving to the tonic of A minor before segueing in A to the chorus. Here the key changes to G and descends through a series of slash chords (G, G/F, G/E, G/D) and reuses the C and C/B of the verses, and the song repeats itself. It’s an unconventional song, one with a patchwork melody that creates conflict between keys—it’s not often you’ll see see a juxtaposition of A major and A minor. Some may call it unruly. I’d call it the work of a songwriter who knows her way around the piano. Rhythmically it’s quite nice too—it breathes and moves organically (fun detail: while the majority of the song is in 4/4, the segue to the chorus sneaks a bar in 2/4—an early use of the hidden Kate Bush time signature change.) It’s not hard to see why Cathy decided to professionally record this one—it’s too good to pass up. Some good ol’ Elton John-y pop for the nice man from Pink Floyd.

Lyrically, “Passing” isn’t a great departure from the demoed songs. Its subject is much the same as “Something Like a Song” or “Queen Eddie”—an elusive figure who makes things magical and exciting. Yet Cathy has honed her skills as a wordsmith to write her best lyric yet. The verses seem to take a spiritual walk through a green moor—Cathy spins poignant phrases like “you mix the stars with your arms” and rhymes them with stuff like “the doom of eternity balms.” The song briefly walks through phrases like this before exploding into G and realizing that what Cathy needs to write is a pop song. “Oh, don’t you throw my love away/I need your loving, I need your loving” is the remedy to the lugubrious tunes she’s composed to date. Finally she’s allowing herself to have fun within a song.

Seven years later, Kate clearly retained a soft spot for “Passing Through Air” that lead her to include it as a B-side to the less cheerful “Army Dreamers.” It’s an odd choice of B-side—”Passing Through Air” has no musical, aesthetic, or thematic resemblance “Army Dreamers”. Why release “Passing Through Air” so long after its recording, when she’d moved forward creatively and become a national treasure? Maybe the track reminded her of a happy time. The excitement of adolescence may have been a sorely needed antidote to the story of early death related by “Army Dreamers.” Even a dark Kate Bush song clings to hope, and a brighter one doesn’t work without anxiety. If you need hope, there’s an abundance of it in Cathy’s demos.

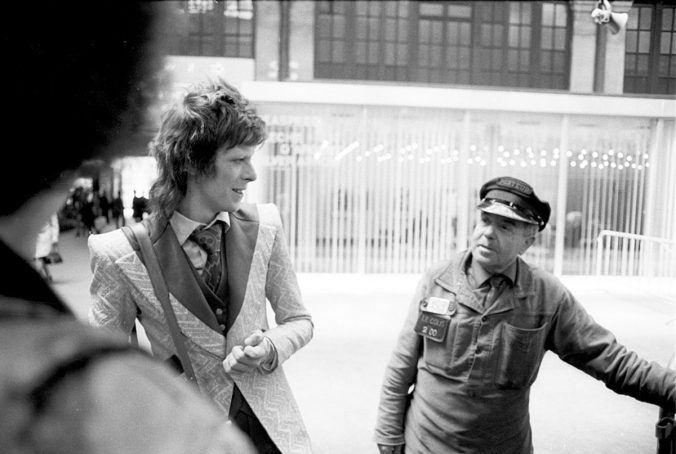

Recorded in 1973 at David Gilmour’s home studio; released as a B-side in 1980. Personnel: Bush—vocals, piano. Gilmour—guitar. Martin—bass. Perrier—drums. Pictures: Hook End Manor, possibly the where the demos were recorded. The studios in Hook End. Kate Bush in Abbey Road.

You must be logged in to post a comment.